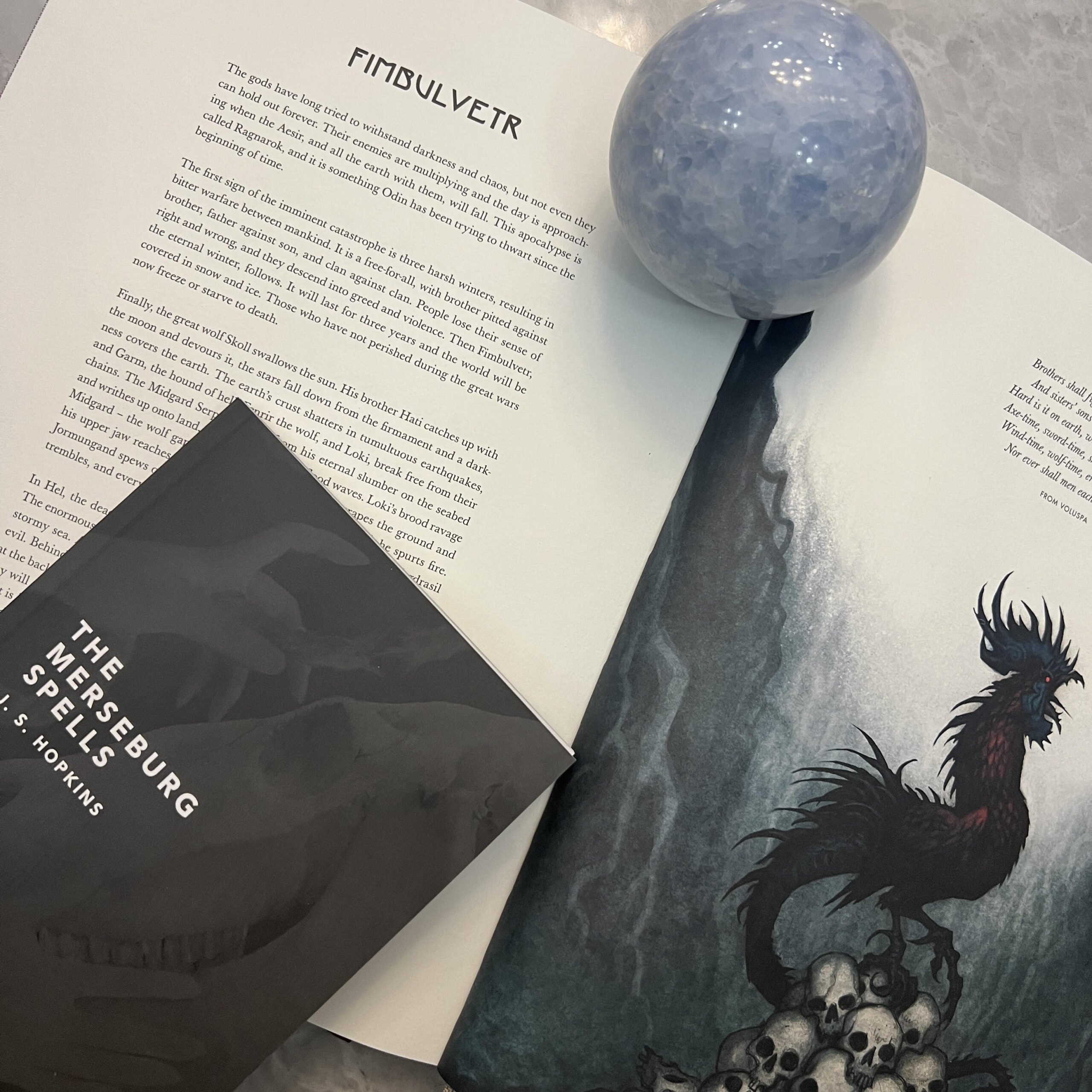

Fimbulvetr

Those Who Favor Fire

The stories of Odin, Loki, and their friends and enemies probably represent just a tiny fraction of the diversity of Norse theology. They are simply the tales that survived; knitted together by nineteenth century cultural historians who wanted a coherent system to mirror that of the classical world.

That doesn’t mean what we think of as Norse mythology is “wrong,” just that it was told and retold in many different ways by many different people.

All of this is prelude to talk about a term we used last week that a few people have asked us about: fimbulwinter, or fimbulvetr.

In Norse mythology (as we know it), the world ends with an event referred to as Ragnarok. It is a bit unclear whether this is an event of sacred time (like the Christian world ending on Good Friday and being reborn on Easter) or a literal one (like the Christian Second Coming).

It is also not entirely clear whether this end was a final termination, or merely a cyclical end and rebirth, with the passage of the people and gods of one age giving rise to another.

Finally, the particular form of this ending is also ambiguous. Some accounts focus on the mythological aspects of magical serpents and hounds. Others highlight more concrete physical changes to the human environment.

Amongst the latter are three consecutive terrible winters in which no sun will shine and no crops will grow. (Some speculate the myth may have been inspired by harsh winters caused by volcanic activity.)

These are fimbulwinter, and they herald the beginning of the end times.

We don’t think that particular apocalypse is upon us yet, but after spending a week in New Orleans during a blizzard, we’re not completely sure.

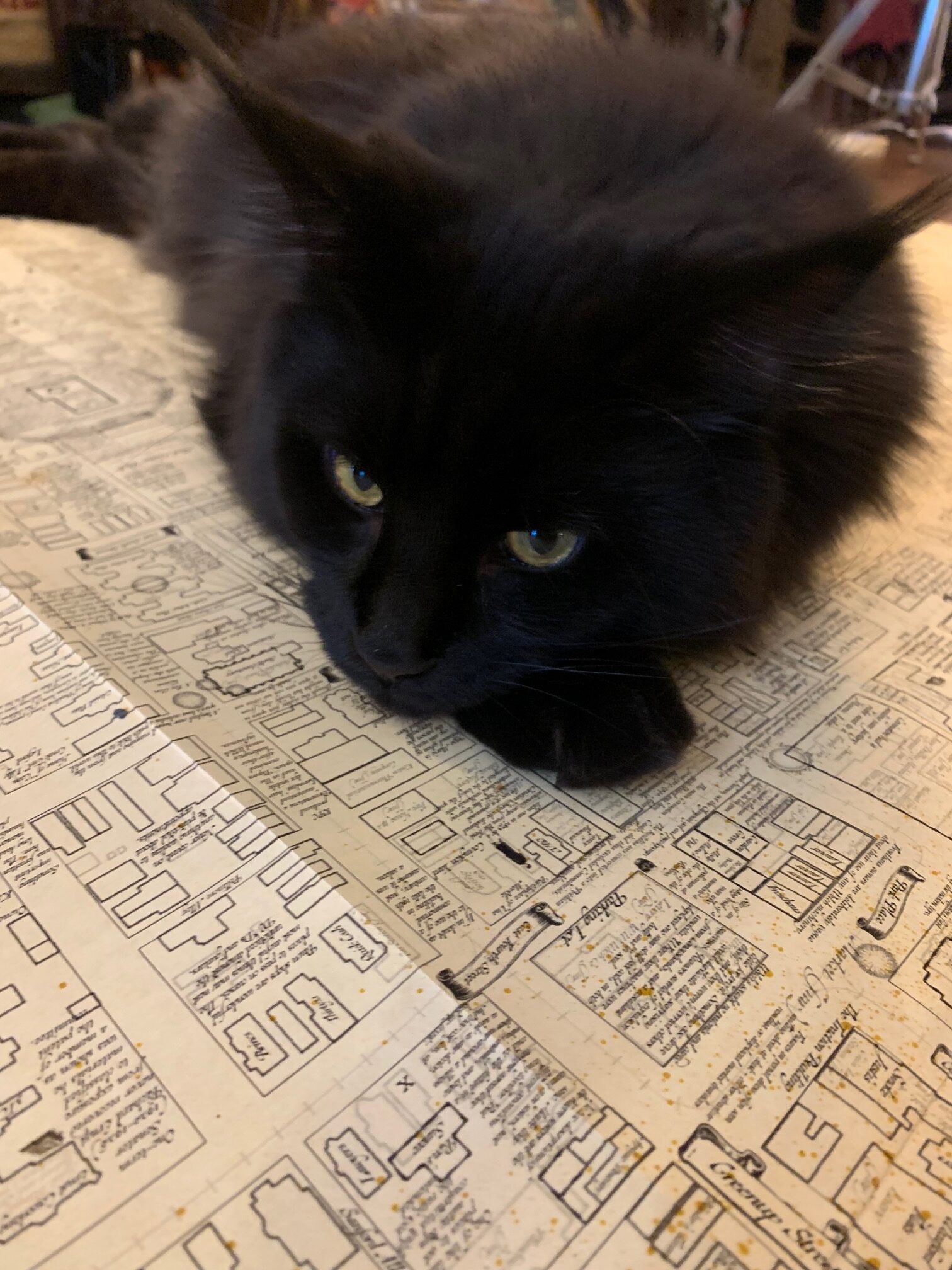

We’ll have a proper tourist report next week, but here is a picture from the (usually bustling) Jackson Square.

We arrived home in time to enjoy some haggis, cranachan, and poetry for our annual January 25th celebration of the Scottish holiday of Burns Night.

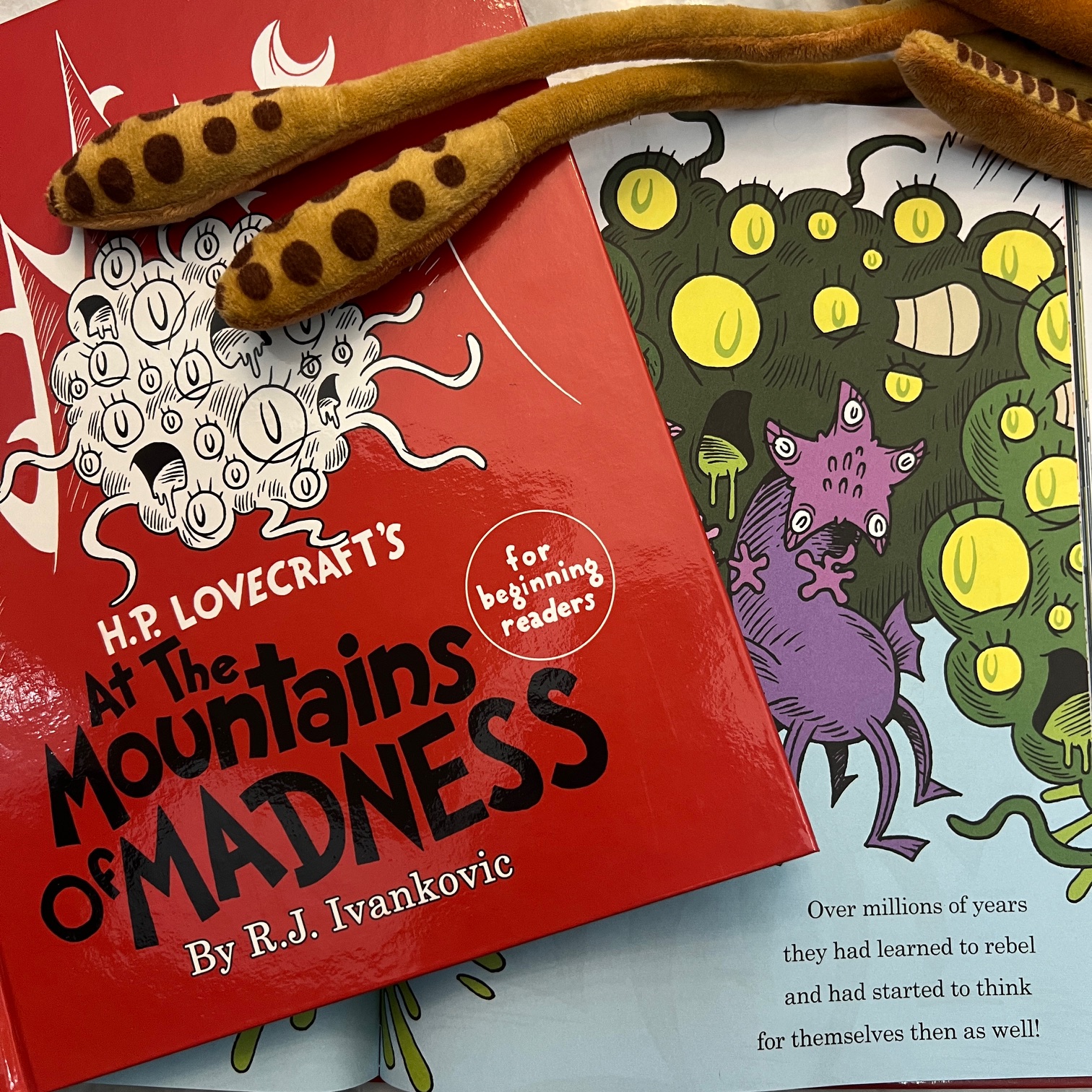

If you’d like to learn more about Nordic myths, we have plenty of books on the topic.

Originally posted to instagram.